The 2008/2009 global financial crisis left a trail of wreckages on Nigeria’s financial market. The Nigerian Stock Exchange All-share Index (NSE-ASI) fell from a height of 66,000 basis points in March 2008 to less than 22,000 points by January 2009. Over 8 trillion Naira (about US$54 billion) or 70 per cent of the total market capitalization of the Exchange was wiped out.

The ripple effects did not spare the money market and the entire monetary policy architecture. The worst hit was the foreign exchange (forex) market that had operated in perpetual volatility with local currency, the Naira, losing 140 per cent of its value between 2008 and 2018. This had led to a renewed vigour on the part of Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) to save the Naira, resulting in several casualties.

Steps in uncertainty

A plethora of fiscal and monetary policy initiatives have been created by the Nigerian government over time aimed at achieving stable exchange rate, single-digit inflation and robust gross domestic product (GDP). Driving this herculean task is the CBN as chief monetary policy authority, while the Ministry of Finance superintends over the fiscal policy landscape.

Since 2013, not less than 20 major monetary policy actions have been introduced by the CBN to address foreign exchange volatility; with little results. Such actions include the “slight” 8.3 per cent devaluation of the Naira in November 2014, revocation of 236 operating licences of Bureau De Change (BDC) operators; closure of the Retail Dutch Auction System (RDAS) and the Weekly Dutch Auction System (WDAS) forex windows, and exclusion of BDCs from the official forex markets.

Others were outright forex restrictions such as the exclusion of 41 (now 45) items from official or inter-bank market window; ban on foreign cash deposits in domiciliary accounts (later reversed).

Prohibition of paying proceeds of foreign-home remittance in Dollar; annual limit on the usage of naira denominated cards, initially $150,000, cut down to $50,000; while daily card usage limit was brought down to $300 per person. Monetary policy authorities also delisted invisibles from official forex window. These include payment of business and personal allowance, educational expenses and medical fees.

Cobra effect

These foreign exchange regulations, many of which have either been reversed or revised, created distortions and triggered massive capital flight in the economy without corresponding investment inflow.

The NSE Foreign Portfolio Investment (PFI) reports showed a total of N470.83 billion (US$2.3 million) inflow in the equity market in 2015 as against N692.39 billion (US$3.46 million) in 2014 – a whopping 47 per cent decline. Total outflow was also massive both in 2014 and 2015: N846.53 billion (US$4.23 million) and N554.24 (US$2.77 million) billion respectively.

Total foreign participation in the Nigerian bourse also showed a decline of N313.85 billion (US$1.56 million) from N1.538.92 trillion (US$7.7 million) in 2014 to N1.025.07 trillion (US$5.12 million) in 2015. Although some improvement was recorded in this aspect, events of the 2019 general elections contributed to wiping off the corresponding gains.

Furthermore, over $20 billion was ‘abandoned’ in domiciliary accounts of citizens who would not risk the then prevailing restrictive foreign exchange policy. Forex volatility heightened as Dollar scarcity bit more severely. Naira depreciation deepened. The JP Morgan removed Nigeria from its Emerging Market Government Bond Index (GBI-EM) 2016.

The Barclays Bank followed suit by delisting the Federal Government bonds from its index. Their actions followed Nigeria’s restrictive exchange rate policy and general macro-economic disequilibrium.

As the local currency continued to depreciate, the parallel forex market witnessed about the worst Naira fall since 2008 with the local currency losing average of 70 per cent of its value between January 2015 and February 2016. It hit N400/US$1 on February 18, 2016, then N320/US$1 in the parallel market.

“This is the effect of demand pressure against supply inadequacy”, said President, Association of Bureau De Change Operators of Nigeria (ABCON), Muhammaded El-Amin Gbadabe.

The forex “insanity” worsened when the Naira “floated” beyond reach on the street market. The local currency depreciating to a historic high of N520/US$1 on February 21 following the announcement of new forex policy regime by CBN the previous day.

The CBN had unveiled a multiple-window forex market policy to address the volatility in the system with the ultimate aim of achieving a convergence between the official and parallel market windows. The CBN spokesman, Isaac Okorafor, had explained that “the new policy will promote transparency and guarantee liquidity”.

Limited gains

The heavy intervention by the apex bank had, in a way, helped in tackling the volatility that ruled the forex market and easing demand pressure on the Naira. Things are looking “good”. JP Morgan and other rating agencies have reversed their earlier positions on Nigeria.

However, these measures seem not to be achieving their objectives. Why? The CBN’s choice of controlled forex policy over market-determined value is at the root of a myriad of challenges that have plagued the economy in recent years. Another major destroyer is the huge resources diverted to subsidising three commodities – petrol, the Naira and electricity.

These are trailed by “soft” economic termites that crawl on government’s social benefits ladder such as the amorphous School Feeding Programme, Trader Money (soft interest-free ‘loans’ of N10,000 (about US$27) to small business owners) and regular sponsorship of religious pilgrimage.

The government spent N2.9 trillion (US$8.3 billion) on fuel subsidy in 2018, largely unappropriated by the National Assembly – the Parliament. The school feeding programme implemented in select states gulps US$1.8 million per day. Government spends upwards of N270 billion on the nebulous school feeding scheme about half of average annual education budget.

Between April 2018 and March 2019, the CBN injected over US$42.3 billion into the forex market to provide the liquidity that would ensure Naira ‘stability’.

Huge ‘leakages’ are said to be happening in the CBN-administered multiple exchange windows. Forex windows include the official/inter-bank rate of N306/US$1, the oft-used Investors & Exporters (I&E) Window hovering at N360/US$1 and the Bureau De Change (BDC) rates slightly above the I&E. Others are the Invisibles (medical expenses, educational fees, tourism); Wholesale, Small & Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and the Parallel market rates. A window was created for fuel importation.

Nigeria’s influential business newspaper, BusinessDay, published in February 2019 that “faceless agents” pocket N32 billion (about US$90 million) profits annually – via arbitrage created by the multiple forex regime. The CBN refuted the claim. Many state governments still sponsor private citizens on religious pilgrimage to Holy Lands at huge expenses.

Pilgrimage is often given preferential and more favourable rate over the I&E window. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has continually warned against Nigeria’s culture of waste and misplaced priorities.

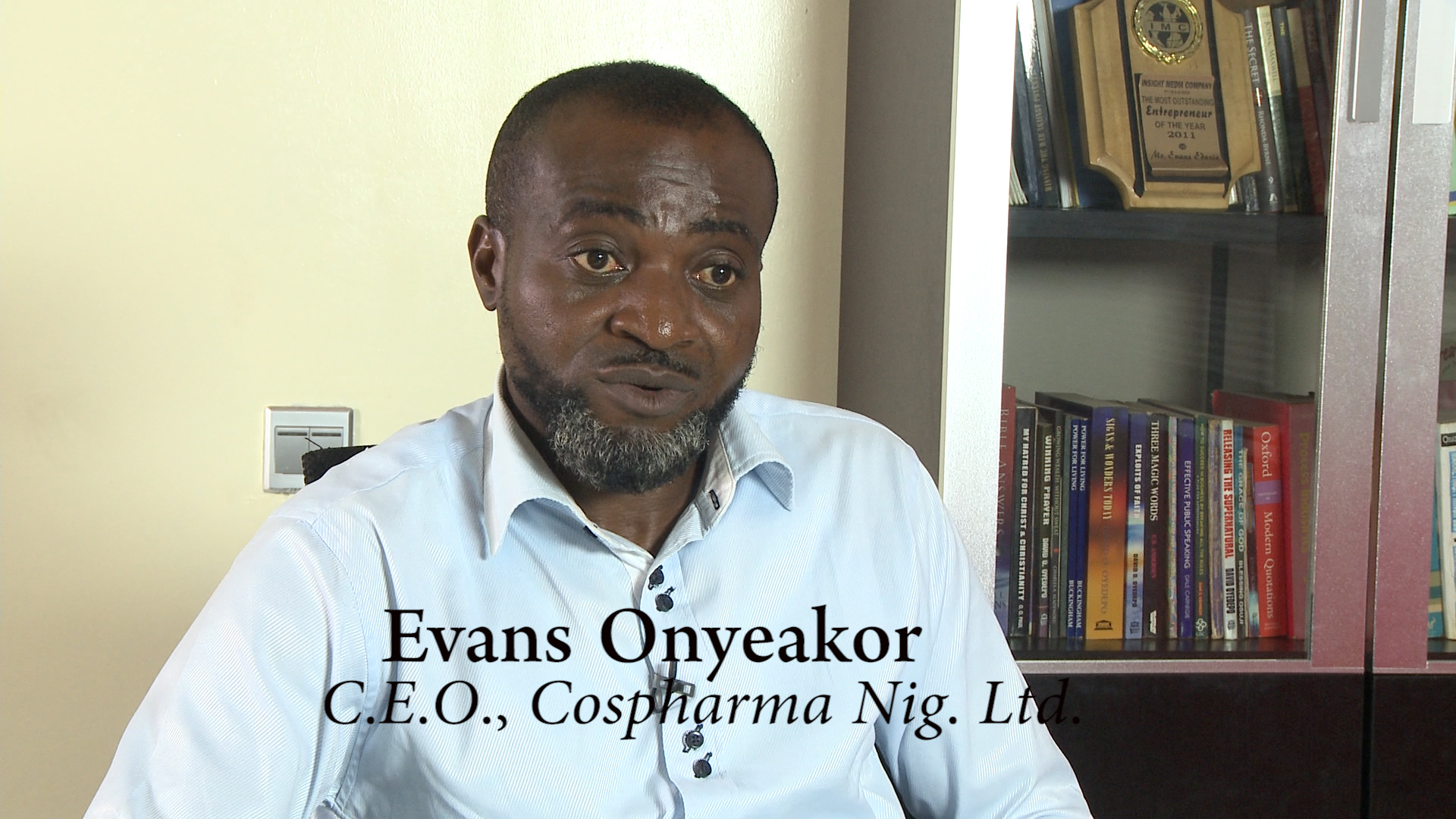

Among other undesirable outcomes is that Nigeria has become the capital of the world’s poorest people with 90.8 million people living in extreme poverty (less than US$1 a day). They constitute 46.4 per cent of its estimated 195.6 million total population in 2018. The Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LCCI) said recently that 2,877 firms shut down in 4 years, due to hostile operating environment.

Nigeria has 13 million out-of-school children – the highest in the world. Unemployment rate stands at 23 per cent as against nine per cent in 2014. Public debt rose from N12 trillion in 2014 to N24.94 trillion (US$81.27 billion) as at March 2019. Debt servicing is 60 per cent of revenue; revenue budget performs average 55 per cent since 2015.

The CBN cannot continue funding cheap dollars which takes a toll on the nation’s foreign reserves. The apex bank should therefore relax its currency management so as to achieve alignment of the official and other market rates, curb round-tripping and attract massive inflow of foreign exchange. Again, mopping up ‘excess’ liquidity, amidst rigid exchange rate regime, will not guarantee the efficiency that free market economy provides.