The Choose France summit of global business leaders held at Versailles on 28 June was French President Emmanuel Macron’s opportunity to push French corporates to seek opportunities beyond their comfort zone.

“40 years ago, France occupied a prominent position in Nigeria,” President Macron tells The Africa Report. “Major French companies occupied leading positions in the construction, manufacturing and logistics industries. More than 10,000 French nationals used to live in Nigeria at that time.”

But, in the early 2000s, challenged by newcomers, French companies lost their way. Michelin and Peugeot, for example, had iconic factories in Port Harcourt and Kaduna respectively – both have since closed.

Today, there are not even a thousand French citizens registered at the embassy in Abuja. “The irony is that many successful foreign [non-French] companies employ French nationals in Nigeria today,” says Macron. Of course, not all French companies lose their nerve in Nigeria.

Despite having little visibility over the pending shake-up of Nigeria’s oil laws known as the Petroleum Industry Bill, TotalEnergies commissioned the largest offshore platform it has ever built, which is now operating at the deepwater Egina field. At its peak production of 200,000 barrels a day, this represents 10% of Nigeria’s entire oil output.

France’s President Emmanuel Macron spent a formative period in Nigeria and is now pushing French corporates to seek opportunities beyond their comfort zone. Of all the qualities French former leader Napoleon Bonaparte prized in his generals – or so the story goes – the most important was luck. France’s President Emmanuel Macron has had his share. For example, the implosion of the centre-left and centre-right candidates in the 2017 elections, allowing him a clean shot at the presidency. His first term has coincided with another piece of ‘luck’; the nativist inward turn of Brexit and US former president Donald Trump has left more space for France on the world stage, especially in Africa.

Macron has a particular vision for France’s relationship with the continent. First, a more open approach to French abuses during and after the colonial era. In 2018, for example, France officially admitted to the murder of Maurice Audin – a member of the Algerian Communist Party tortured to death by the French army during the war of independence. In Rwanda in May, Macron recognised France’s role in the 1994 genocide.

Macron is also pushing an activist economic diplomacy. It is bound up in a critique of France Inc., which he sees as too timid in its approach to global markets beyond its comfort zones. “40 years ago, France occupied a prominent position in Nigeria,” President Macron tells The Africa Report. “Major French companies occupied leading positions in the construction, manufacturing and logistics industries. More than 10,000 French nationals used to live in Nigeria at that time.”

But, in the the early 2000s, challenged by newcomers, French companies lost their way.

Michelin and Peugeot, for example, had iconic factories in Port Harcourt and Kaduna respectively – both have since closed. Today, there are not even a thousand French citizens registered at the embassy in Abuja. “The irony is that many successful foreign [non-French] companies employ French nationals in Nigeria today,” says Macron.

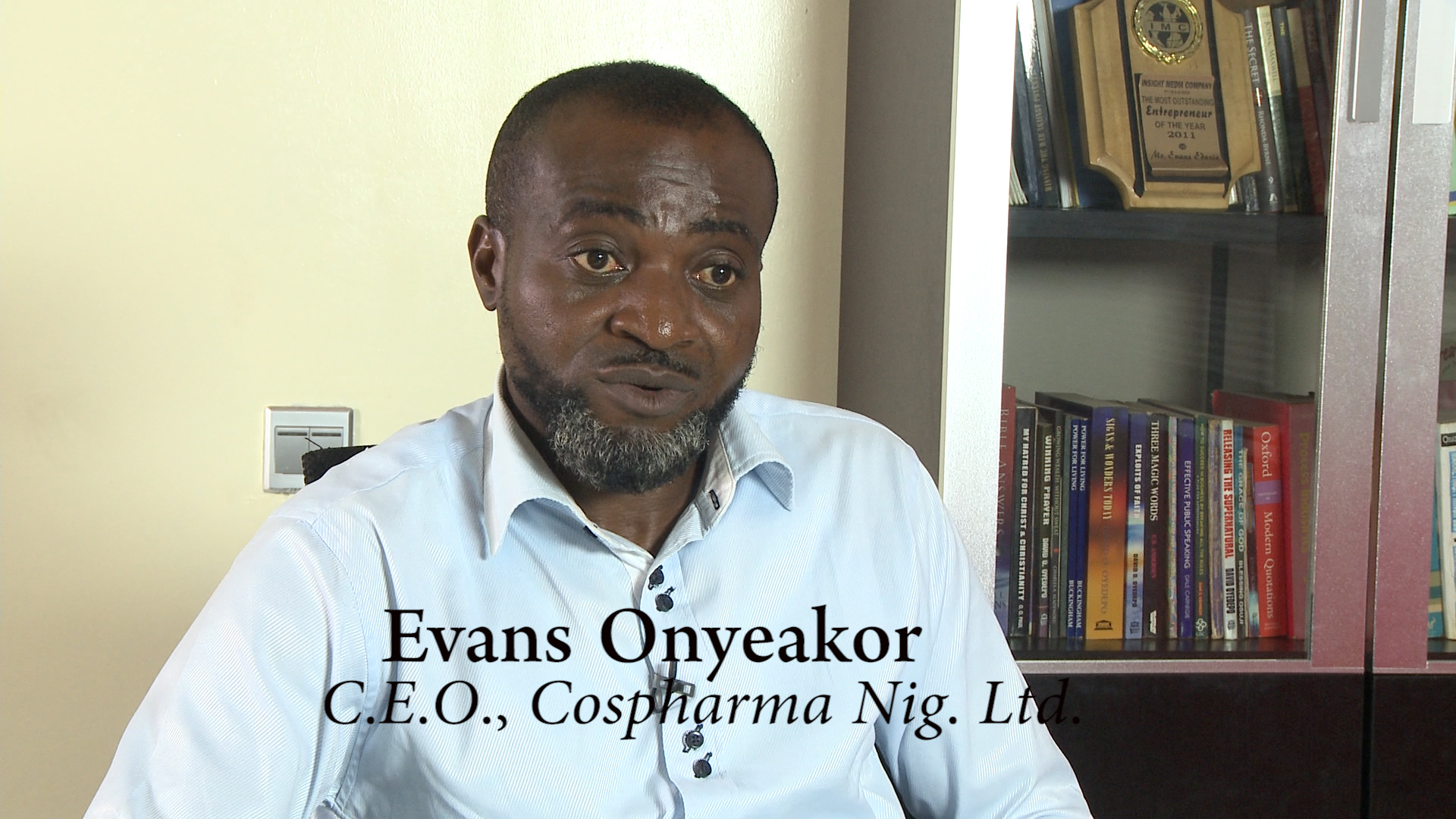

Nigeria is where Emmanuel Macron’s relationship with the continent began. In 2002, he spent six months as an intern at the French embassy in Abuja, and discovered a country that has little in common with more familiar Françafrique haunts like Abidjan, Dakar or Libreville.

“[Nigerians] have no inferiority complex about France because the country is not on their radar,” Macron told Antoine Glaser and Pascal Airault in a recent book. “I was very happy [in Nigeria]. There was so much to do, with extremely entrepreneurial people, very creative, with whom I was able to have a relationship of equals in a very spontaneous and natural way.”

The ambassador thought it would be useful for the young intern to spend time outside the official French diplomatic circuits and sent him to see Jean Haas, who is currently the managing director of Relais International consultants. Since the 1980s, Haas has been building a network of connections to Nigeria’s private sector. Certainly, ‘hard’ factors like rising insecurity and poor infrastructure make life tough for businesses in Nigeria.

An editorial in Lagos newspaper The Guardian from February 2007 sounds eerily familiar today: ‘Michelin’s exit brings to the fore a number of issues,’ the paper opined. ‘The failure of government to provide an enabling environment for tyre manufacturers, the energy crisis and the effect on the cost of doing business, as well as the abuse of presidential waivers by some privileged Nigerians.’

But there are three ‘soft’ factors, too, that affect French companies in Nigeria – a lack of personal connections, a lack of nerve and a flexibility deficit.

First, networks. In recent decades French multinationals have heavily rotated their expatriate staff members, and boardrooms increasingly lack a ‘Monsieur Afrique’ to help maintain networks. “Business in Nigeria is principally a story about people, and the connections between them – if you don’t have that, it is hard to operate,” says Haas. [The Africa Report]