Recently, the Central Bank of Nigeria was directed by President Muhammadu Buhari to block food importers’ requests for foreign currency in a bid to boost local agriculture in the country.

The policy according to the government comes in continuation of its efforts to ban the use of foreign exchange to import dozens of items including staple foods and rice.

This move by the Federal Government was criticized as one that did not take into consideration the low capacity of local farmers in the country. And as a result, food prices especially rice have almost doubled twice its original price. Also, the policy coincided with a rise in food prices, which has been blamed on insecurity in some of the country’s main food producing areas.

Although, there are indications that domestic rice production has increased over the years, experts in the private sector believe that the policy of restricting food imports does have some merits, but it cannot be introduced in isolation. They identify regulatory risk as the biggest challenge faced by businesses in the country.

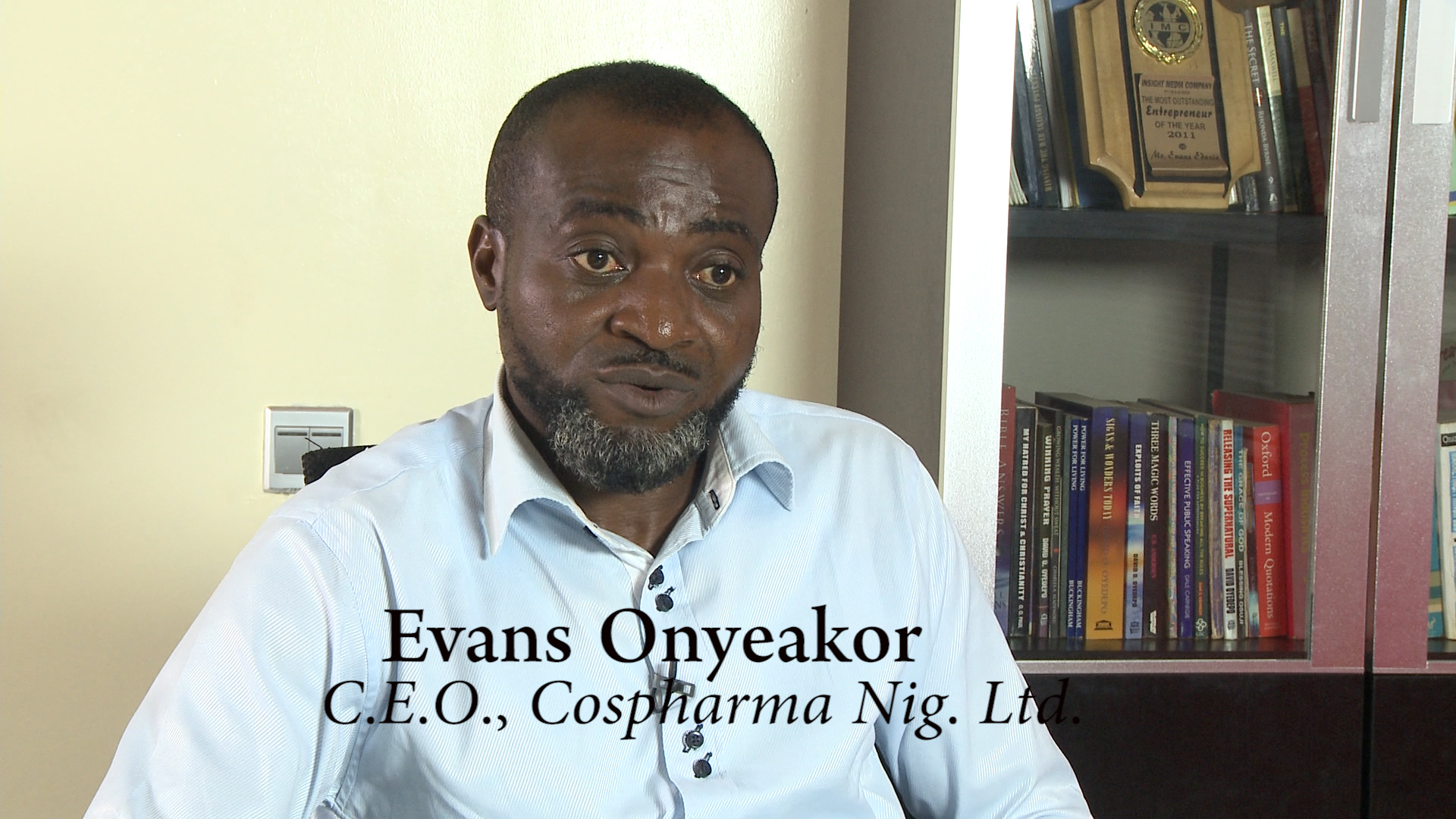

At a forum tagged ‘Regulatory 4.0 with the theme “foreign exchange restrictions on food imports and implications for regulating and growing the Nigerian economy”, Stakeholders called for national strategy in policy formation. Organized by the Intergrity Organisation Limited, the event was attended by professionals as well as experts from across various sectors of the economy.

Professor of Economics and Leadership, Prof. Pat Utomi, argues that regulatory risk is a major factor for the failure of most businesses in the Country. According to him, a national economic strategy is a question of urgency for the government.

“The biggest risk in doing business in Nigeria is regulatory risk. The regulator is more likely to kill a company than any market risk. We can do isolated industrial policy to those areas of which our endowments allow us to become competitive globally and dominate that value chain, but we must have a clear national strategy about specific areas that we want to dominate as global leaders.’’ Utomi said.

He explained that negative legitimacy would not take the country anywhere but instead would destroy businesses and as well lead to increase in unemployment rate. According to him, systematically certain sectors of the economy have been wiped out by an unthinking regulator acting.

He called on the Nigerian government to think through the consequences of its policies before implementation them, urging players in the food industry to educate each other on such consequences because the economy belongs to everyone.

“Part of our duty as players in this, is to say to ourselves ‘look this economy belongs to all of us’, and we begin to educate ourselves on the consequences,” he said.

Data from Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) indicate that Nigeria spent nearly $2.9bn (£2.4bn) on food importation in 2015 and by 2017 that figure had risen to $4.1bn.

Source: The National Bureau for Statistics

Food commodities such as sugar, wheat flour, fish, milk, palm oil, pork, beef and poultry are produced in the country, however, domestic farmers have not been able to meet the demand of the country’s over 200 million people, hence the need for imports. With the foreign exchange ban Nigerian farmers will now have to increase production.

Director-General of the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LCCI), Mr Muda Yusuf, also spoke on the role of regulators as crucial to economic development explaining that they mean well for the country but the problem was in strategy development and implementation.

“Unfortunately we don’t have regulators in government, who actually listen or engage with experts so that you can have the right kind of strategy to achieve the desired result. There are too many regulations in the country and the damage this is doing to the economy is enormous. To do business with integrity in Nigeria today is a tall order,” he added.

According to him, many businesses have transited to becoming players in the informal sector as a result of challenges of regulatory compliance. He argues that the emphasis should be on building domestic capacity for the development of the country, as smugglers had taken over businesses in Nigeria and the country was losing because smugglers don’t pay taxes.

What happens if food prices go up?

The economic theory of demand and supply suggests that reducing the supply of something will increase the price. As such, there is a general belief that if domestic supply cannot immediately replace what was once imported, Nigerians will end up paying more for their food or possibly face a crisis of food shortage in the country.

Between 2015, when the foreign exchange restrictions for rice came into effect, and early 2017, the price of a 50kg bag of rice went from $24 to $82. It later fell in mid-2017 to $34. But in June this year, the price stood at $49.

The crux of the matter

Nigeria’s agricultural sector, which remains a major employer, has suffered years of neglect as the country has spent decades relying on oil to provide much-needed foreign exchange and government revenue. It is estimated that just over a third of available land is being cultivated in the country as not all available agricultural land is being used.

Following a drop in oil prices a few years ago, there are indications that the country has renewed its interest in agriculture. Economy watchers believe that if this enthusiasm can be converted into greater investment then the country should be able to produce more food and possibly join major exporters of certain foods in the world.